Between the 1890s and 1970s in Australia, it is estimated that at least 100,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were forcefully removed from their families. They are known as the Stolen Generations. While the trauma of the Stolen Generations remains rooted within Indigenous Australia, more First Nations children are being taken today than ever before.

The Stolen Generations

The Stolen Generations are the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children that were forcefully removed from their families between the 1890s and 1970s under the Australian government’s assimilation policies that sought to “bread out” Aboriginal cultures.

The removal of Aboriginal children was legally enforced by the 1909 Aborigines Protection Act.

In 1997, the Bringing them Home report estimated that one in three Aboriginal children was taken from their families.

Despite a National Apology in 2008 by the then-Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, more Aboriginal children are being taken from their families today by the Department of Community Services (DoCS) than during the Stolen Generations.

In November 2018 in New South Wales, a new set of adoption laws (The Children and Young Persons Care and Protection Amendment Bill) made it easier for First Nations children to be adopted without parental consent.

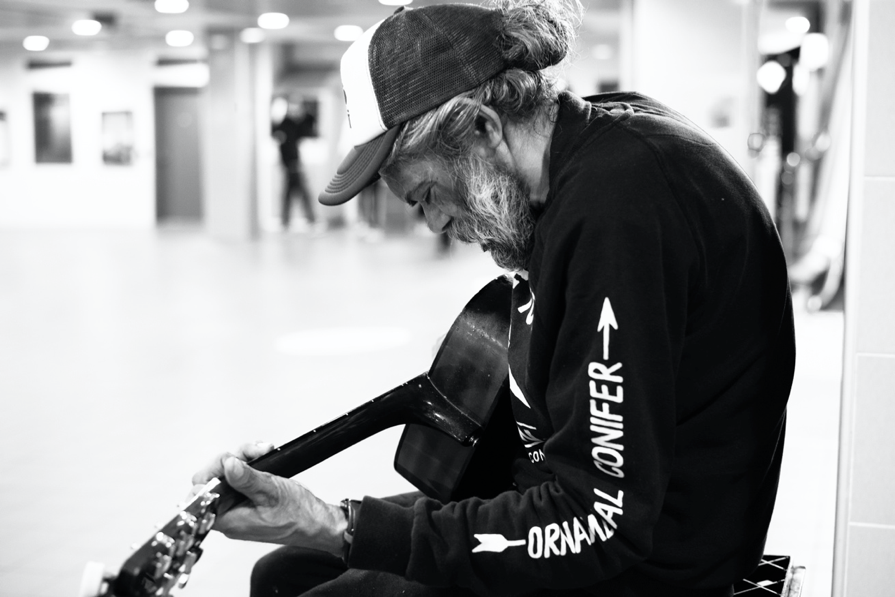

He is there, leaning on two empty crates, guitar in hand, head down. Only his black and silver beard protrudes from the cap shading his face. “I’m learning to fly, but I ain’t got wings…”, he sings Tom Petty’s words as hundreds of passersby come and go. It’s 2pm in Central Station and Sydney-siders return, bellies full, to their workplace. Some stop to drop a coin in the pink Tupperware box lying by the busker’s thongs. That is when his face raises with a smile, followed by a “thank you, have a nice day”.

Clarence Sibley has been busking in Sydney for the last 18 years. Few know that the Aboriginal man who is often spotted at Central Station’s tunnel and Broadway’s shopping mall is one of the Stolen Generations. “I was taken from my parents and placed in a children’s home run by the Roman Catholic Church when I was a couple of months old,” Clarence explains before biting into his chicken burger. “It’s good we’re coming in here, I was starting to get cold outside,” he remarked as we entered Broadway’s Oporto.

“I’ve got 5 brothers and 1 sister. All of us except the youngest brother are Stolen Generations.” The Waka Waka boy was reunited with his mother in Grade 7. “Our sister put me and my brother on a train to Ingham and then mom picked us up and we lived there for the next four years.” He counts on his fingertips covered in calluses. “Grade 8, 9, 10 and one year of work at a sugar cane mill.”

Clarence’s wrinkled face lights up when he mentions his college studies in Brisbane. “I was studying to become a primary school teacher,” he begins, “I got to my first year when mom passed away in 1987. So I didn’t get back to it much. After that, I stayed in Brisbane working for Australia Post until 1996 when my brother took me to Melbourne. That’s when I started buskin’.” It wasn’t until 2000 that Clarence decided to attempt university studies again in Wollongong. “But then I got more bad news,” the Aboriginal busker sighs. “My brother’s missus passed. After the second time, I thought, nah… So I went back to buskin’.”

Clarence learned to play the guitar when he was 9 years old. “Not far from the home was a seminary where people were training to become priests. There was one student there who gave me guitar lessons. The first song I ever played was Bob Dylan’s Blowin’ in the Wind,” he gazes towards his guitar tucked by his side. “I need my guitar to support myself…” he begins, “I often think, if I didn’t know how to play then I would be into a lot of financial troubles.”

In New South Wales alone, an estimated 6,200 Aboriginal children were stolen between the 1890s and 1970s and tens of thousands more nationwide. The 1997 report Bringing them Home judges that one in three First Nations children was removed from their families. Through assimilation policies, the Government strived to ‘breed out’ Torres Strait and Aboriginal cultures by assimilating them to white society. Today, while many Australians regard the Stolen Generations as a past issue, others speak of a second, much larger Stolen Generation.

In Hyde Park, troops gather at Archibald’s fountain. Over a decade has passed since Kevin Rudd’s National Apology, yet many still wait for words to become action. “Sorry means you don’t do it again,” resonates from the crowd marching towards Parliament. On this Sorry Day, the Grandmothers Against Removals called out. Youthful troops led by Bruce Shillingsworth, an Aboriginal artist and activist, emerge from the city. “Let’s join them and show our support!”, he yells out to the hundreds of howling and drumming teenagers on Climate Strike. The Climate March heads towards the Sorry Day parade and soon they all melt into a common voice, a common fight. Aboriginal flags flutter as placards reading

“Kids in Culture, Not in Care”, “Aboriginal Control of Aboriginal Child Welfare” invade Macquarie Street.

“Let me give you some statistics,” David Shoebridge grasps the microphone, while a banner reading “Stop Stolen Generations” is raised on the Parliament’s fence. “Since the 1997 Bringing them Home report, the number of Aboriginal kids taken across this country has increased fivefold.” Boos crescendo. “Since Kevin Rudd’s National Apology in 2008,” Shoebridge continues, “the number of Aboriginal children taken in this state has more than doubled.”

“Just in November of last year, this place, my workplace,” the Greens MP points to the NSW Parliament, “passed a fresh set of laws that made it easier for First Nations kids to be taken from their families and then adopted.” Shoebridge refers to the new adoption laws which legalise adoption without parental consent in New South Wales.

In 2012, the Northern Territory’s Coordinator General for Remote Services Olga Havnen was sacked after alerting about a second Stolen Generations. The government official’s report revealed that while only $500,000 was spent on support measures for impoverished Aboriginal families, $80,000,000 was invested on their surveillance and the removal of their children.

A frail yet tenacious-looking Elder comes forth as the crowd hushes. Aunty Hazy Collins founded Grandmothers Against Removals after her youngest grandson was taken from her daughter by the Department of Family and Community Services. “This system has been flawed from Day 1,” she begins stoically, “it is flawed because it was founded on genocide.” The rally clamours as the drums roll. “They couldn’t wipe Aboriginal people out by massacring them, murdering them. So the next step was to do it by the theft of our children.”

“Shame,” the mob yells. “No mother goes into a delivery room and delivers an orphan,” Aunty Hazy’s voice resonates across Macquarie Street as her fierce gaze turns to the Parliament. “We have White People sitting up there, dictating to us, First Nations peoples, what is best for us, how we should live. Well to them I say fuck off.” The crowd roars with the drumbeats. “Nobody that walks this Earth has the right to abduct, nor abuse, nor adopt our children. It’s time for this Government to be held accountable.”

As applause burst, the microphone is handed to a fairer-skinned teenager named Matthew. “I was removed 13 days after my 14th birthday, on the 28th of June,” the 16-year-old clears his throat and raises his head, “two Department workers and four police officers showed up at my house and took my sister and I away.” His face twitches as his speech intensifies, “I’ve never been more disgusted! I spent Christmas on my own with a social worker and haven’t seen my sister in three years. And I’m one of the lucky ones, I live in a Youth Refuge so I’m not homeless.”

There is no new or second Stolen Generations ; the Stolen Generations that began in the 1890s never ended. More First Nations children are being taken today than ever before in Australian history. In the year preceding the 2008 National Apology, 9,070 First Nations children were in out-of-home care. In 2015, seven years after Rudd proclaimed that “the injustices of the past must never, never happen again”, their number had nearly doubled to 15,455. Despite representing only 5.5% of their age group, more than a third of the children forcibly removed are Aboriginal – a rate rising to over 66% in the Northern Territory. Assimilation has been camouflaged in bureaucratic jargon.

Meanwhile in Central Station, an Aboriginal busker keeps singing behind his grey and black beard: “Well some say life will beat you down, break you heart, steal your crown. So I’ve started out, for God knows where. I guess I’ll know, when I get there…” The Waka Waka man raises his face and smiles : “To see people happy caused by me makes me happy.” As Tom Petty sings, Clarence Sibley is learning to fly without wings.

Rachel B. HÄUBI